The City Makers is an empowering tribute to women reshaping urban India

The City Makers is an empowering tribute to women reshaping urban India The City Makers is an empowering tribute to women reshaping urban India

The book is a fascinating introduction to the world of community-led governance and along the way, it busts several myths about housing and urban poor.

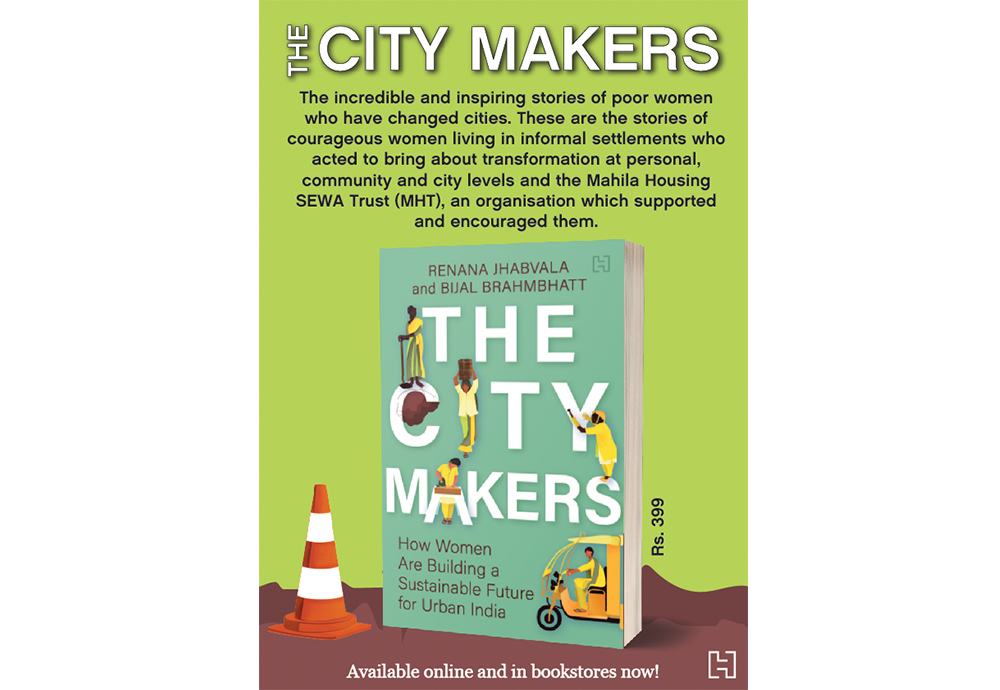

What does urban development look like when it is driven by women from low-income communities residing in slums? How do they move from the margins to a seat at the decision-making table? Where do they get the skills, knowledge and training to secure basic services and improve the living conditions of their families? These are some of the questions that Renana Jhabvala and Bijal Brahmbhatt address in their book The City Makers: How Women Are Building a Sustainable Future for Urban India (2020), published by Hachette India.

Jhabvala is the chairperson of SEWA Bharat, a federation of institutions providing economic and social support to women in the informal sector and the chairperson of SEWA Grih Rin Limited, a company providing affordable housing finance to underserved low-income households. Brahmbhatt is the director of Mahila Housing Trust, overseeing operations across eight Indian states and 36 cities. She advocates for equitable housing rights for the urban poor, alternative pro-poor building norms and development regulations suitable for affordable housing.

The City Makers is a fascinating introduction to the world of community-led urban governance in a format that weaves together stories and statistics in an enjoyable manner. Readers unfamiliar with subjects such as housing finance, slum electrification, land rights and climate resilience need not worry because the authors have written in a style that is clear and accessible. At the same time, they do not compromise on depth or complexity. Their material is well-researched, insightful, rich in detail and far from boring.

Jhabvala and Brahmbhatt are concerned about the fact that the urban poor are often deliberately kept out of the housing market because “housing for the poor is seen as a ‘welfare’ measure; policymakers do not see urban poor housing as a productive asset”.

Their research evidence challenges “the myth that housing is not a productive asset for the poor” and calls on financing institutions to “release funds both for basic infrastructure and construction of units if the urban poor are to have a chance at living in adequate shelters and improved habitats”.

This book does an excellent job of breaking stereotypes associated with people living in informal settlements who are often unfairly regarded as lazy, unproductive and with criminal tendencies. It focuses on their entrepreneurial skills, their leadership potential and their belief in hard work rather than accepting handouts. The authors achieve this without fetishising their poverty or being patronising. This respectful approach gives their book a quality of integrity which all authors must aspire to while interacting with and writing about marginalised communities.

Jhabvala and Brahmbhatt write, “It is important to understand that for low-income communities around the world, houses are considered key assets, in both rural and urban areas. A house functions as a shelter, a commodity and an investment. Home ownership confers collateral in credit markets, social status and security in the event of natural and human-made disasters like floods, earthquakes and riots. A house, however small, offers opportunities to increase incomes through small-scale, home-based economic activities.”

This book demonstrates that their vulnerability often stems from the lack of opportunity not of motivation. People who work in the informal sector cannot produce a salary certificate as proof of income if they wish to apply for a loan to cover the costs of home improvement. Moreover, housing finance institutions are reluctant to lend money because they cannot assess repaying capacity when there is no fixed income every month. The other problem is that if the title to a house is informal, it is not possible to mortgage their house as leverage.

How did the Mahila Housing Trust beat these obstacles? What kind of financial products were created to enable borrowing without the threat of exploitation by moneylenders? How did the physical transformation in homes and neighbourhoods impact emotional well-being, the perception of safety and social relationships?

In answering these questions with examples from Ahmedabad, Jaipur, Ranchi and other cities, the authors celebrate the perseverance of the women who steered the change by organising themselves and liaising with city officials.

This book is persuasive because it locates its arguments in grassroots initiatives that have reported successes and also indicates areas of concern. While a participatory model is empowering because it is built on community ownership, there are risks involved. Manual errors are possible. Data gathering practices can pose ethical dilemmas for community leaders who are sometimes forced to choose between recording accurately and protecting community members from legal consequences. Moreover, surveyors can face harassment.

That said, Jhabvala and Brahmbhatt’s book must be read primarily because it presents urban women from low-income communities as agents of change and not as victims of patriarchy or as passive beneficiaries of services from the state. Through conscious acts of engaged citizenship, they are shaping the present and future of India’s cities. Their contributions might be unsung but they have already left their mark.

(Chintan Girish Modi is a writer, educator and researcher who tweets @chintan_connect)